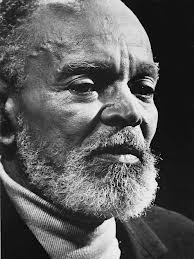

Chester Bomar Himes was an African American writer born in Jefferson City, MS, on July 29, 1909. His parents were to Joseph Sandy Himes Sr. and Estelle Bomar Himes; his father was a peripatetic black college professor of industrial trades and his mother was a teacher at Scotia Seminary prior to marriage.

Chester Bomar Himes was an African American writer born in Jefferson City, MS, on July 29, 1909. His parents were to Joseph Sandy Himes Sr. and Estelle Bomar Himes; his father was a peripatetic black college professor of industrial trades and his mother was a teacher at Scotia Seminary prior to marriage.

At age twelve, Himes’ father began teaching at Branch Normal College (now the University of Arkansas). He and his brother Joseph Jr., were made to sit out a gunpowder demonstration by their mother as punishment for bad behavior. The boys decided to conduct the experiment without adult supervision, which resulted in an explosion that blinded Joseph Jr. The aftermath of this tragedy had a profound effect on how Himes viewed race relations later in life. When Joseph Jr. was rushed to the nearest hospital, he was denied treatment due to his race.

“That one moment in my life hurt me as much as all the others put together,” Himes wrote in The Quality of Hurt:

“I loved my brother. I had never been separated from him and that moment was shocking, shattering, and terrifying….We pulled into the emergency entrance of a white people’s hospital. White clad doctors and attendants appeared. I remember sitting in the back seat with Joe watching the pantomime being enacted in the car’s bright lights. A white man was refusing; my father was pleading. Dejectedly my father turned away; he was crying like a baby. My mother was fumbling in her handbag for a handkerchief; I hoped it was for a pistol.”

A short time later, the family settled in Cleveland, Ohio. His parents’ marriage was an unhappy one which eventually ended in divorce.

Himes attended East High School while in Cleveland. Later, during his time as a freshman at Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio, he was expelled for playing a prank. He was arrested in 1928 for armed robbery and sent to Ohio Penitentiary. He was sentenced to hard labor for 20 to 25 years.

While in prison, Himes wrote a number of short stories, which were eventually published in national magazines. Later, he would state that his prison writings and publications were a means of earning respect from guards and fellow inmates. It also helped him to avoid personal violence.

Himes’ first stories appeared The Bronzeman magazine starting in 1931. His work later appeared in Esquire magazine in 1934. Of particular note was a story titled, “To What Red Hell”. His debut novel “Cast the First Stone”, dealt with the catastrophic 1930 prison fire Himes witnessed while serving time at Ohio Penitentiary. It was published almost ten years after it was written, most likely due to Himes’ unusually candid treatment—for that time period—of a homosexual relationship. Originally written in the third person, it was rewritten in the first person in a more “hard-boiled” style (which Himes would eventually become famous for) and posthumously republished unabridged in 1998 as “Yesterday Will Make You Cry”.

Himes was transferred to London Prison Farm that same year and in April 1936, was released on parole into his mother’s custody. He continued to write following his prison release, while working part-time jobs. It was during this period that he came into contact with author, Langston Hughes. Hughes facilitated Himes’s contacts with the world of literature and publishing.

In 1936 Himes married Jean Johnson (who he later divorced), Four years later, he moved to Los Angeles, where he worked as a screenwriter and also produced two novels, “If He Hollers Let Him Go” which contains many autobiographical elements — is about a black shipyard worker in Los Angeles during World War II struggling against racism, as well as his own violent reactions to racism. His next novel, “The Lonely Crusade” that charted the experiences of the wave of blacks who were part of the Great Migration. Himes’s novels encompassed many genres including the crime novel/mystery and political polemics, exploring racism in the United States. His work centered on African Americans in general, especially in two books that are concerned with labor relations and African-American workplace issues. He also provided an analysis of the Zoot Suit Riots for The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP.

Hines screenwriting career came to an abrupt halt Jack Warner of Warner Brothers heard about him and said, “I don’t want no niggers on this lot.”

Himes later wrote in his autobiography:

“Up to the age of thirty-one I had been hurt emotionally, spiritually and physically as much as thirty-one years can bear. I had lived in the South, I had fallen down an elevator shaft, I had been kicked out of college, I had served seven and one half years in prison, I had survived the humiliating last five years of Depression in Cleveland; and still I was entire, complete, functional; my mind was sharp, my reflexes were good, and I was not bitter. But under the mental corrosion of race prejudice in Los Angeles I became bitter and saturated with hate.”

By the 1950s Himes had decided to leave the United States and settled permanently in France. Himes like the country in part due to his popularity in literary circles. While in Paris, Himes’ was the contemporary of the political cartoonist Oliver Harrington and fellow expatriate writers Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and William Gardner Smith.

Himes was most famous for a series of Harlem Detective novels featuring Coffin Ed Johnson and Gravedigger Jones, New York City police detectives in Harlem. The novels feature a mordant emotional timbre and a fatalistic approach to street situations. Funeral homes are often part of the story, and funeral director, H. Exodus Clay is a recurring character in these books.

The titles of the series include “A Rage in Harlem, The Real Cool Killers, The Crazy Kill, All Shot Up, The Big Gold Dream, The Heat’s On, Cotton Comes to Harlem, and Blind Man With A Pistol”; all written between 1957-1969.

“Cotton Comes to Harlem”, was made into a movie in 1970, which was set in that time period, rather than the earlier period of the original book. A sequel, “Come Back, Charleston Blue”, was released in 1972, and “For Love of Imabelle” was made into a film under the title “A Rage in Harlem”, in 1991.

“Cotton Comes to Harlem”, was made into a movie in 1970, which was set in that time period, rather than the earlier period of the original book. A sequel, “Come Back, Charleston Blue”, was released in 1972, and “For Love of Imabelle” was made into a film under the title “A Rage in Harlem”, in 1991.

It was in Paris in the late 1950s that Chester met his second wife Lesley Himes, née Packard, when she was assigned to interview him. She worked as a journalist for the Herald Tribune, where she wrote her own fashion column, “Monica”. He described Lesley as “Irish-English with blue-gray eyes and very good looking”. In her, he found someone who didn’t judge him for his race and he also admired her courage and resilience.

In 1958 he won France’s Grand Prix de Littérature Policière and a year later, Himes suffered a stroke, which led to Lesley quitting her job so that she could nurse him back to health. She cared for him for the rest of his life, and worked with him as his informal editor and proofreader. After a long engagement, they were married in 1978.

Lesley and Chester faced adversities as a mixed race couple living in that time period however, they were resilient and prevailed. People close to the author recalled his life with Lesley as one filled with unparalleled passion and great humor. Their circle of political colleagues and creative friends included; Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Malcolm X, Carl Van Vechten, Pablo Picasso, Jean Miotte, Ollie Harrington, Nikki Giovanni and Ishmael Reed. Their Bohemian life in Paris eventually led them to the South of France and finally on to Spain, where they remained until Chester’s death in 1984.

Some within the publishing industry regard Chester Himes as the literary equal of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. Ishmael Reed has said, “[Himes] taught me the difference between a black detective and Sherlock Holmes” and it would be more than 30 years until another Black mystery writer, Walter Mosley and his Easy Rawlins and Mouse series, had even a similar effect.

In 1996, his widow Lesley Himes went to New York to work with Ed Margolies on the first biographical treatment of Himes’s life, entitled The Several Lives of Chester Himes, by long-time Himes scholars Edward Margolies and Michel Fabre, published in 1997 by University Press of Mississippi. Later, novelist and Himes scholar James Sallis published a more deeply detailed biography of Himes called “Chester Himes: A Life (2000)”.

A detailed examination of Himes’s writing and writings about him can be found in “Chester Himes: An Annotated Primary and Secondary Bibliography” compiled by Michel Fabre, Robert E. Skinner, and Lester Sullivan (Greenwood Press, 1992).

Himes was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.

In May 2011, Penguin Modern Classics in London republished five of Himes’ detective novels from the Harlem Cycle.

On a personal note:

Chester Himes, along with Walter Moseley and Robert B. Parker were HUGE influences on my writing in terms of both content and style. I owe these men a great debt and I honestly don’t think that I’d be a writer today, had I not experienced reading their work(s).

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

If He Hollers Let Him Go, (1945)

Lonely Crusade, (1947)

Cast the First Stone, (1952)

The Third Generation, (1954)

The End of a Primitive, (1955)

For Love of Imabelle, alternate titles The Five-Cornered Square, A Rage in Harlem, (1957)

The Real Cool Killers, (1959)

The Crazy Kill, (1959)

AUTOBIOGRAPHIES:

The Quality of Hurt (1973)

My Life of Absurdity (1976)